By David J. Barboza

Robby searching for the right shot on the curvy, leafy streets of Rustic Canyon. The photos in this post were taken by the author unless otherwise noted.

With so many SurveyLA reports coming out these days, one might be tempted to think the project is wrapping up. The truth is, fieldwork is ongoing. In fact, we’re only in “Group 5” (of 9), which is our shorthand for Bel Air, Beverly Crest, Westchester, Playa del Rey, Brentwood and Pacific Palisades. I recently had the pleasure of tagging along with Kari Fowler and Robby Aranguren of Historic Resources Group, one of the consulting firms doing the fieldwork for SurveyLA (and an employer of mine, in the interest of full disclosure).

Hopefully this post helps to de-mystify SurveyLA and also highlights the important role that you play in feeding us information about historic places that matter to you. Fieldwork is where the rubber meets the road, where, after much preparation, specially trained people have to make decisions about what places to document in detail as being significant for their architecture or socio-cultural connections, and how to categorize and describe those places.

After we met up in Brentwood, it was quickly decided that in the interests of avoiding epic construction-related traffic on Sunset on the way home, we should caravan over to a neighborhood in Pacific Palisades called Rustic Canyon, where we would be spending most of the day. Here’s a map of the area:

A map of Rustic Canyon and vicinity. We started towards the north, where Sunset meets Brooktree. Source: Google Maps.

Right off the bat one of the most typical problems we would face that day struck: view-blocking fences and foliage. How do you document something you can’t see or can’t see very well? As it turn’s out, there’s a survey code for that, QQQ, which means more research is required. Survey teams do what they can from the public-right-of-way and using aerial imagery, but sometimes, a complete architectural description just isn’t possible.

Visibility was not always at an ideal level for survey work.

The day was mostly focused on places that are remarkable for their architecture and we ran into the work of two architects in particular: Marshall Lewis and Ray Kappe. Marshall Lewis was first, with the David Fisher House. The team settled on Late Modern as the style for this unorthodox piece of residential architecture.

The David Fischer House, a 1970s design by Marshall Lewis.

Places that are documented as individual resources for architecture get a detailed architectural description that, in addition to overall style category, covers construction materials for the building’s structural system as well as its surfaces, entry areas, doors, roof type and materials (which was fun on the example above), fenestration (i.e. the types and arrangement of openings in the building), landscaping and more. It is said that the Eskimo have 50 words for snow, and that seems like an apt metaphor for the richness of vocabulary architectural historians bring to bear describing each facet of a building’s design. Quite interesting to hear!

Soon after, we came across our first Raymond “Ray” Kappe designed house of the day, the Katzenstein Residence (1974). It is a late and expressionistic example of the Mid-Century Modern style.

The Katzenstein Residence (1974) by Ray Kappe.

The team wasn’t doing detailed analysis of every building they came across. An earlier recon phase of fieldwork had resulted in a list of properties that would be examined in more detail later. Informing all of this is research and historic place suggestions from a variety of sources. One of those sources is Gebhard and Winter’s Architectural Guidebook to Los Angeles. Chapter 3 (Pacific Palisades, South) in the 2003 edition of that book has background information on a few of the houses we documented, including the nearby Harrison House.

Ray Kappe struck again just up Brooktree Road with the Howard Gates Residence, a post-and-beam Mid-Century Modern design perched at the top of a steep hill. Looking at it through branches it came off as a giant tree house.

The Howard Gates Residence (1961) by Ray Kappe

Speaking of Kappe, did you know that his own house is in the area? We passed by it but didn’t document it because it’s already designated as Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #623. It shows off Kappe’s style while gracefully navigating a difficult site.

Although the streets of Rustic Canyon generally lack sidewalks, you do see people walking around. Purely by chance, we’re pretty sure we saw John Densmore, who is probably best known for being a drummer for The Doors. That’s not making it into SurveyLA of course, but one issue that does come up is how to handle places that are associated with major historical figures, including entertainment industry types. It came up for us later that day as we followed up on leads about the James Whale house. Whale directed the 1931 film version of Frankenstein based on Mary W. Shelly’s 1818 novel. Whale met a tragic and macabre end himself, committing suicide by drowning in his pool. The team checked out two houses but ultimately concluded more research was needed to determine if Whale lived in one of them during his most productive years.

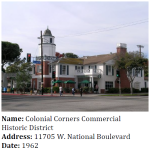

On a lighter note, lunch was great. We headed over to a charming little commercial part of Pacific Palisades around Sunset and Swarthmore for a bathroom break (which can be a tricky part of survey logistics) and some delicious Mexican food. Surveying this neck of the woods wasn’t on the day’s agenda though. Here’s the streetscape:

Looking south at Sunset and Swarthmore. Image: Google Maps Street View.

The David Hyun House (1960) was definitely a highlight. David Hyun was the first architect of Korean descent in the United States. Hyun’s father was active in the movement for Korean independence under Japanese occupation in the early 20th century. Hyun designed the Japanese Village Plaza, an interesting outdoor mall with nods to east Asian architecture near 1st and Central in Little Tokyo. For his own house, Hyun chose a Modern post-and-beam design with a pergola-like roof structure. The large front windows expose an interesting spiral staircase. Also notable is the way the plan of the house makes way for mature trees that were apparently on the site when it was built.

The house David Hyun designed for himself (1960).

Towards the end of the day we ran into more Marshal Lewis houses. The photo below shows one of them. If the houses we saw that day are any indication, Lewis is definitely a fan of “non-traditional” roof forms. This Late Modern design had many different roof pitches and directions of pitch as well as an un-shingled section of roof at one corner which exposed the structural system of rafters and purlins below.

A Late Modern Marshall Lewis house (1974)

The last house of the day was also a treat. The Alfred Neuman Residence was built by Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. (a.k.a. Lloyd Wright). This 1950 gem is perched atop a hill on over 2.5 acres and had been owned by Dianne Keaton. As befits a day when many of the buildings were hard to see, this one was as well, but you can see more of it here.

The Alfred Newman Residence by Lloyd Wright (1950)

Thanks to Kari and Robby for showing me around. It was a great day, and I look forward to reading about the findings for the Brentwood-Pacific Palisades Community Plan Area. In the meantime, it’s certainly not too late to tell us about your favorite historic LA places. The information ends up in the field and makes SurveyLA more effective. It’s a team effort!

Kari recording the team’s observations in SurveyLA’s FiGSS Geographic Information System.

We’re back!

We’re back!